The First Kaime: The Birth of Interest-Bearing Banknotes in the Ottoman Empire (1840)

Introduction

In January 1840, the Ottoman Empire took a bold leap into the modern age of monetary policy with the issuance of its first paper currency: the kaime-i nakdiyye-i mutebbere. Unlike traditional banknotes, these kaime were revolutionary for one key reason—they bore interest. This short-lived yet groundbreaking experiment marked one of the earliest examples of state-issued, interest-bearing money in global economic history.

This article delves into the origins, mechanisms, motivations, and legacy of the 1840 kaime, drawing on a blend of archival research and modern economic historiography.

⸻

Why 1840? The Tanzimat & a Treasury in Crisis

The kaime’s birth coincided with the launch of the Tanzimat reforms in 1839, a sweeping modernization effort aimed at reorganizing the Ottoman administrative, military, and financial systems. With reforms came massive state expenditures—but the Empire faced critical liquidity problems. Traditional borrowing from Galata bankers or foreign financiers proved insufficient or prohibitively expensive.

Faced with this fiscal bottleneck, the Ottoman government sought an internal solution. Thus, the kaime was introduced in 1840 as a form of state debt, circulating as paper money that would pay interest to the bearer—a hybrid between a treasury bond and a banknote.

🔍 Source: Pamuk, Şevket. Liquidity Preference and Interest-Bearing Money: The Ottoman Empire 1840–1851. Financial History Review, Vol. 11, Issue 1, 2004.

⸻

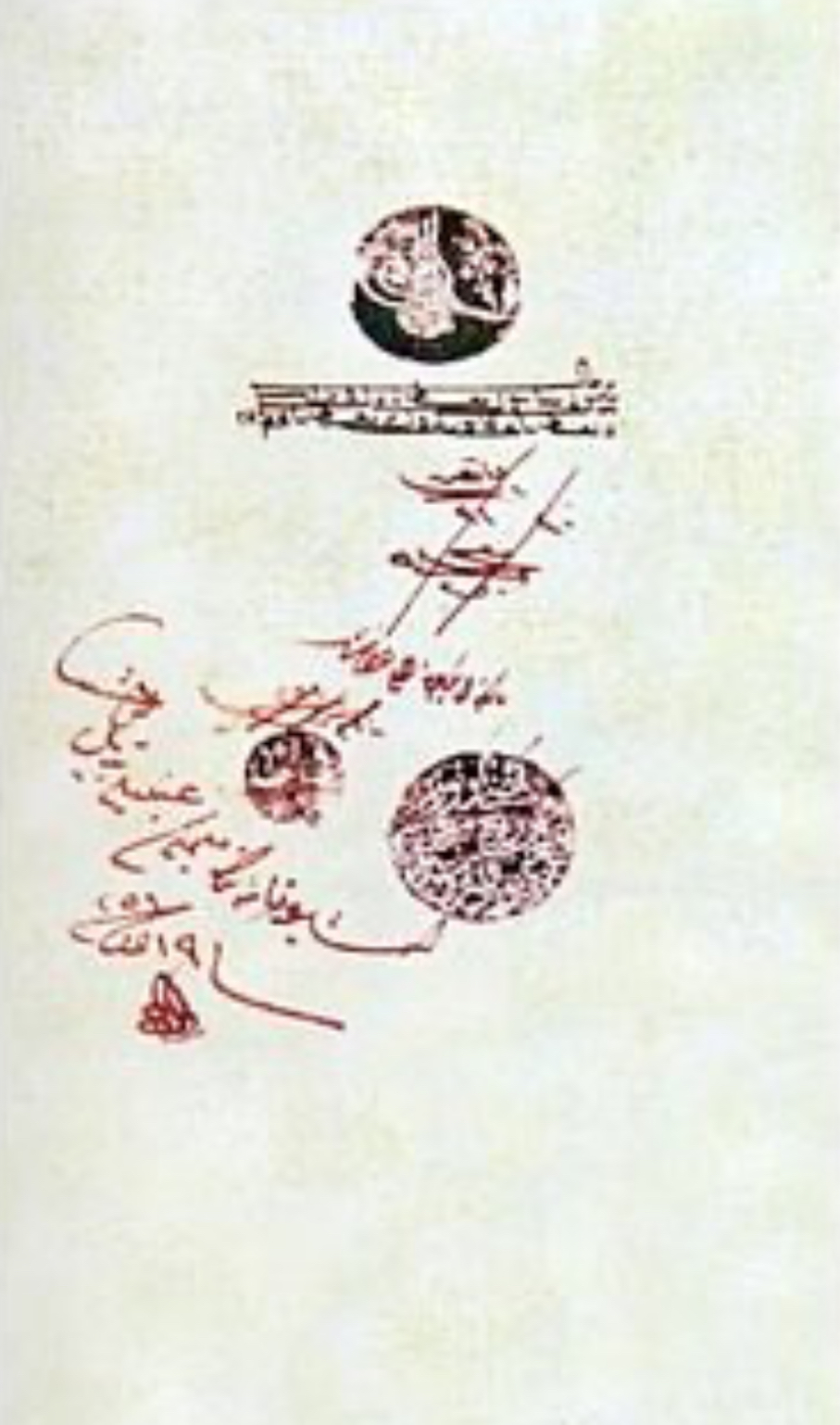

Design and Structure: Handwritten Notes with the Sultan’s Seal

The first kaime notes were handwritten, individually signed, and stamped with the tughra (imperial cipher) of Sultan Abdülmecid I. Printed on thick, durable paper, they came in denominations such as 500 kuruş, which at the time equaled roughly £4.5 sterling.

To ensure credibility, these notes were registered at the treasury, and were backed by the full guarantee of the state.

🔍 Source: Central Bank of Turkey Museum. History of Banknote Printing in the Ottoman Empire

https://sanalmuze.tcmb.gov.tr

⸻

The Interest Mechanism: An Innovative (and Risky) Proposition

What truly set these notes apart was their 12.5% annual interest rate, payable to the holder. The kaime would accumulate interest over eight years, and were redeemable through the treasury.

This structure made them function as interest-bearing debt instruments. Public confidence was bolstered by the interest feature, encouraging adoption in a society accustomed to coin-based transactions.

🔍 Source: Bulgarian National Bank Economic Review, “The First Interest-Bearing Banknotes in the Ottoman Empire,” 2005

https://www.bnb.bg/bnbweb/groups/public/documents/bnb_publication/pub_np_seemhn_02_05_en.pdf

⸻

Setting the Rate: Did the Empire Copy the West?

The Ottoman Treasury set the rate at 12.5% per annum, a figure not borrowed directly from European monetary systems but rather reflective of domestic borrowing costs. In fact, government borrowing from local financiers in Istanbul and the provinces often ranged between 12–15%.

Thus, while the kaime were inspired by Western notions of public credit, the interest rate was locally grounded.

🔍 Source: Pamuk, Ş. (LSE). “The Ottoman Economy and European Capitalism, 1820–1913.”

https://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/GEHNConferences/conf6/Conf6-SPamuk.pdf

⸻

Circulation and Usage

Initially, the kaime circulated mostly in Istanbul and were accepted for tax payments, official salaries, and commercial transactions. They were treated as full legal tender, though they were always understood to represent a claim on future payment with interest.

While the interest followed the bearer, it was only paid at redemption. This meant that the person holding the note when it matured would collect the cumulative interest—not the previous owners. In the secondary market, notes sometimes traded at a premium or discount, reflecting their accrued value.

🔍 Source: Pamuk, Ş., Liquidity Preference and Interest-Bearing Money, 2004.

⸻

Coins vs. Kaime: Two Worlds, One Treasury

Unlike kaime, Ottoman coins (gold, silver) contained intrinsic value and did not yield any return. Kaime, on the other hand, represented a liability of the state—the first time Ottoman paper carried not only nominal value but time-based financial return.

This made the kaime particularly attractive in times of cash shortages, but also vulnerable to overissuance and inflation.

🔍 Source: Istanbul History Foundation. Finance in Ottoman Istanbul.

https://istanbultarihi.ist/571-finance-in-ottoman-istanbul

⸻

The Collapse: From Innovation to Devaluation

By 1844, new series were issued with a reduced interest rate of 6%, but the system ultimately buckled under the weight of war financing—particularly the Crimean War (1853–1856). The flood of new issues (to cover deficits) eroded public confidence. By the 1850s, kaime notes were trading at deep discounts, and the Empire ceased interest payments.

The government pivoted to non-interest-bearing banknotes and began efforts toward the founding of a central bank, leading to the eventual establishment of the Imperial Ottoman Bank in 1863.

🔍 Source: Bulgarian National Bank Review, 2005.

⸻

Legacy for Collectors

Today, the 1840 kaime are among the rarest and most historically significant Ottoman notes. Their combination of imperial authority, handwritten issuance, and built-in yield makes them a prized specimen in any collection.

Collectors should note the unique calligraphy, tughra marks, and condition of paper to assess authenticity and value. Surviving examples are typically housed in museum collections or elite private holdings.

⸻

Conclusion

The Ottoman Empire’s first kaime banknotes were more than just an early attempt at paper money—they were financial instruments designed to stabilize a reforming empire through public credit. While short-lived, they provide an extraordinary glimpse into the crossroads of Islamic finance, European modernization, and Ottoman innovation.

For collectors, historians, and economists alike, the kaime stand as both a technical marvel and a cultural milestone.

Comments • 0

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!